|

I am happy to announce that in February I joined the San Francisco Estuary Institute as an Environmental Scientist with the Urban Nature Lab in the Resilient Landscapes program. Environmental Scientist is bit of a generalized HR name in place for what I really do, which is work with amazing teams of ecologists, landscape architects, and designers to apply ecological theory and practice to biodiversity conservation and sustainability planning in urban landscapes.

I am still working remotely from home, so--although my physical office is in Richmond, California, nestled on the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay--I've returned to the towering redwoods and slinking banana slugs of Santa Cruz. The place where my formal educational journey really began. It's been pretty amazing to roam some of my old haunts and think back to my burgeoning interest in conservation science & planning, natural history, and agroecology. Somehow, I managed to turn those early exciting moments of discovery into a lifelong career. I feel pretty grateful.

0 Comments

The St. Louis Audubon Society invited the Billiken Bee Lab to speak at their annual meeting. We heartily accepted and proceeded to have a fun night talking about birds, bees, mosquitoes, backyard habitat conservation, and urbanization.

I tag-teamed the talk with Gerardo Camillo, Nina, and Trey, which is one of my favorite ways to give a presentation. It keeps things a bit more dynamic! You can catch the presentation here. The talk itself begins at 00:17:00.

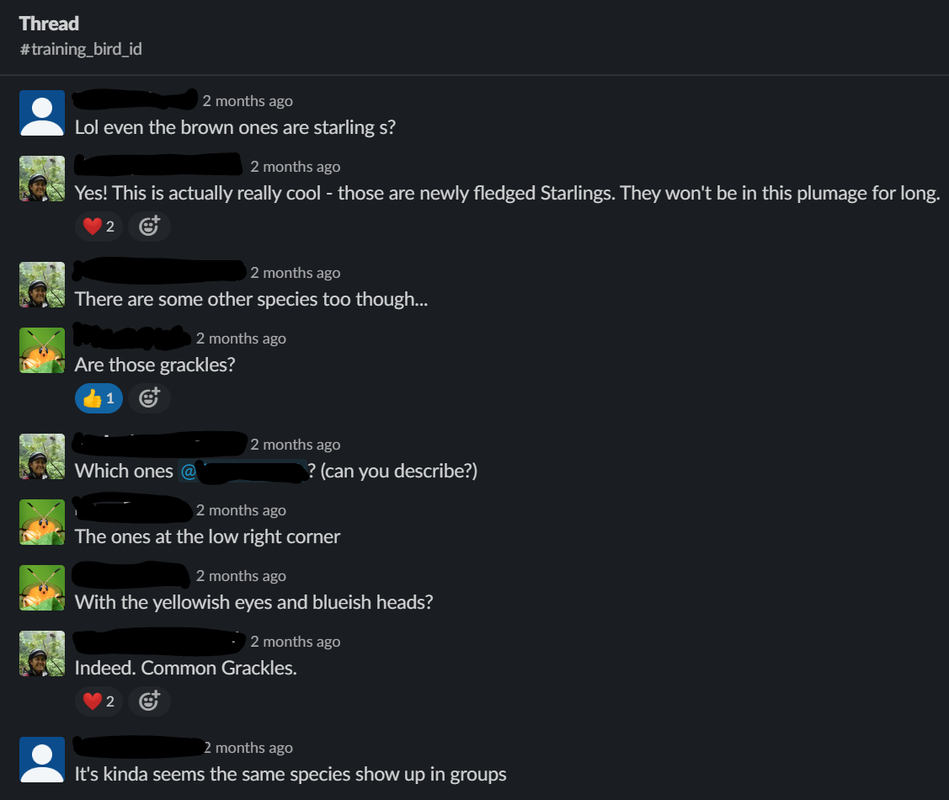

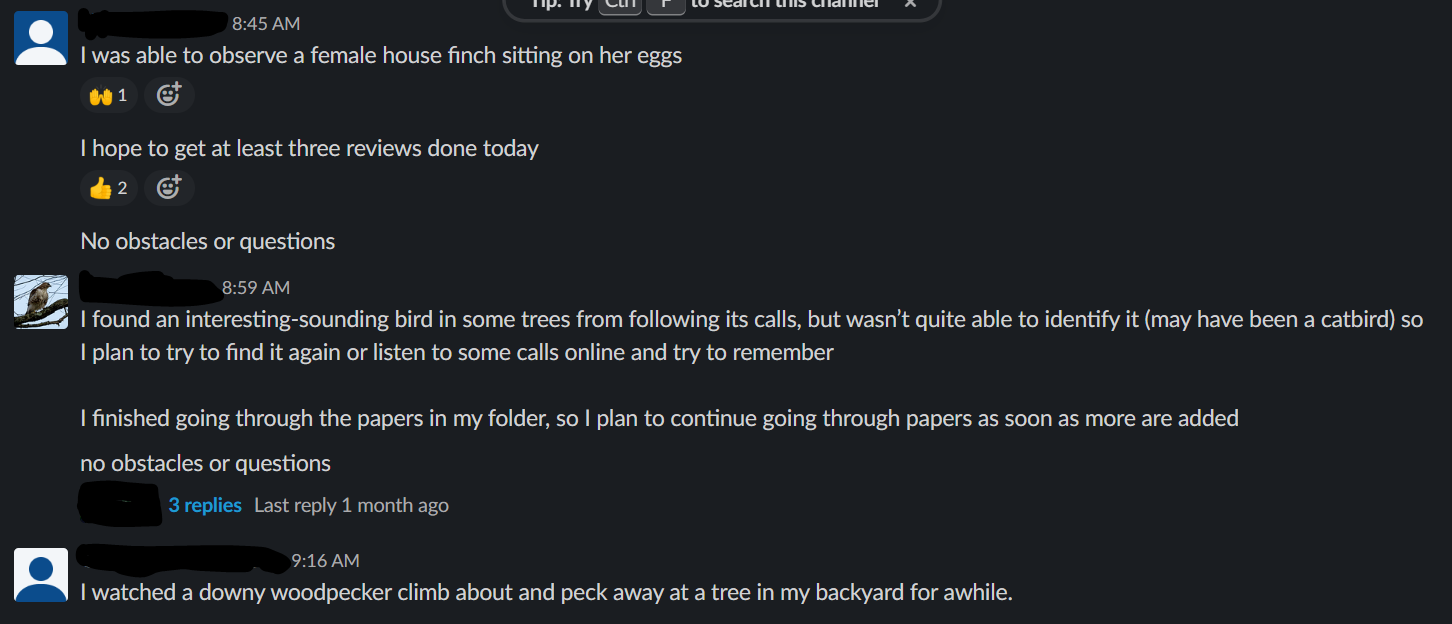

In the summer of 2020, Washington University's Tyson Research Center held their summer Undergraduate Fellows Program completely virtually. Among other research skills, we in the Tick & Wildlife Team focused on bird identification.

We were very pleasantly surprised that it was incredibly rewarding, fun, and uplifting to "bird" together virtually.

Each week, we selected a live cam to watch together.

And we would meet at a specific time to "bird" and chat about the birds we were watching in real time via Slack.

Because we wanted to observe birds in other parts of the world in different time zones, we also selected long recorded live cam segments and played them at the same time while we chatted (e.g., the Allen BirdCam offerings).

We found other live cam platforms to bird from, including: Houston Audubon: Bolivar Flats Bird Cam Littlehouse Prairie Village, Kansas, USA Septimo Paraiso Lodge Feeding Platform, Ecuador One of our most successful activities was to combine our weekly birding session with our weekly anti-racism in science and conservation training: Virtual bird watching in the Monterey Bay Aquarium Aviary for #BlackWomenWhoBird @BlackAFInSTEM And it got the students outside and really excited about birds,

Other tasks we included in our virtual bird id training:

1. Download and sign up for a Merlin account. Using Merlin, id one bird from your window or backyard. 2. Follow #BirdingWhileBlack on twitter 3. Take the eBird essentials course and read about tips for eBirding from home 4. Read and learn about the differences between eBird Yard, Incidental, and Complete lists. 5. Each day this week try to identify and enter into eBird at least: 1 bird into your yard list and/or 1 "incidental" or "complete" list at another (safe, socially distanced) location. 6. At least 3 times this week, go outside with a notebook to a location where you can sit and observe a single individual bird for at least 5 minutes (or until it flies away completely). Spend the first 2-3 minutes just OBSERVING this individual bird. Try to get a sense of what it is up to. Then spend a few minutes jotting down some notes, what are the behaviors you observed? What do you think these behaviors mean? What other questions do your observations bring up? 7. Download and work on Thayer's bird quizzes. We also watched other bird and birding related videos: Birding Wile Black: A Candid Conversation Jason Ward's Birds of North America TedGlobal, Washington Wachira: For the love of birds TedxAmsterdam, Arjan Dwarshuis: What birdspotting can teach us about conservation Listened to podcasts and stories: BirdNote: House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) BirdNote: Why Birds Stand on One Leg Short Wave - Crows: Are They Scary or Just Scary-Smart? Ologies: Plumology (FEATHERS) with Dr. Allison Shultz Coronavirus Live Updates: Do Those Birds Sound Louder To You? An Ornithologist Says You're Hearing Things Ologies: Pelicanology (PELICANS) with Juita Martinez Watched webinars associated with our bioacoustics research: WildLabs Tech Tutors, Carlos Abrahams: How do I perform automated recordings of bird assemblages? WildLabs Tech Tutors, Tessa Rhinehart: How do I scale up acoustic surveys with AudioMoths and automated processing? Soundscapes to Landscapes Training Series: Validating Bird Calls

Of course, nothing beats in-person instruction. But during our end-of-season meetings with each Fellow, they highlighted our group birding sessions as among their favorite activities of the summer. In addition to meeting our learning objectives, our virtual birding expeditions also helped us relax and bond as a group. I highly recommend it!

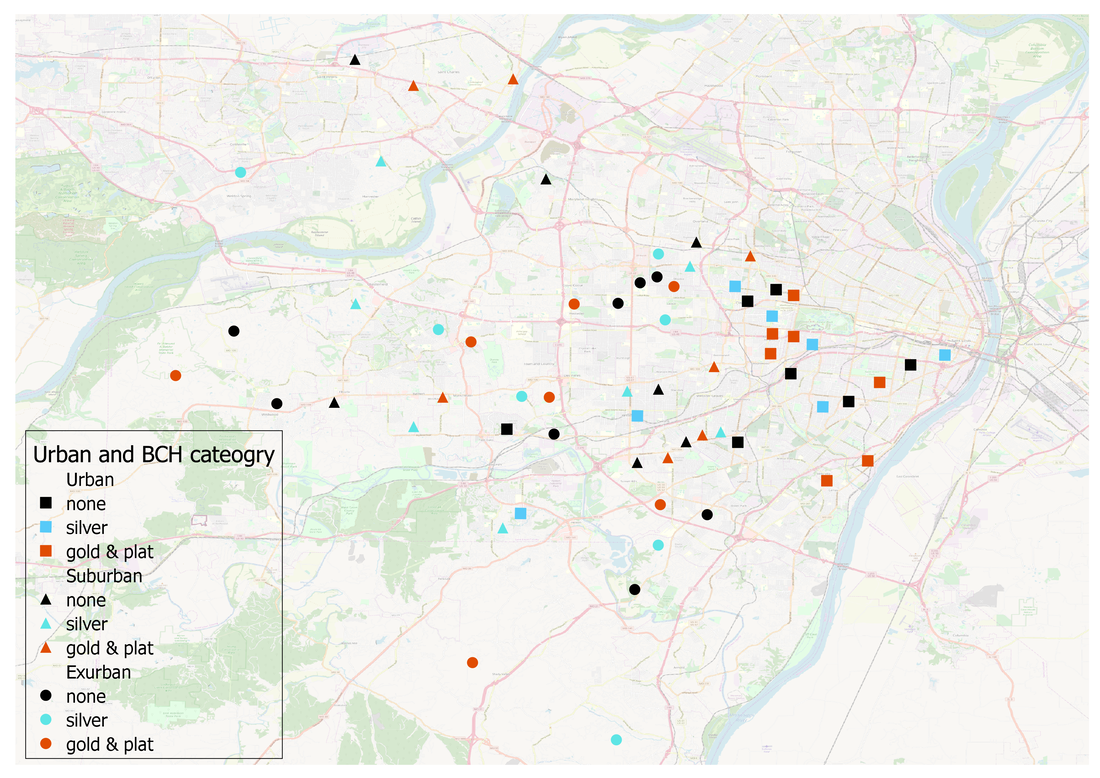

I have been planning and preparing for over a year to begin studying birds, their predatory behaviors, and their own predation risk, in residential backyards along a gradient of urbanization in the St. Louis metropolitan area, Missouri, USA. Along with the rest of the world, however, my plans have drastically changed due to COVID-19, and instead I am committed to keeping the curve flat, staying at home, and finding a path forward. I am switching gears to employ a no-contact, socially-distanced, stay-at-home sampling regime. My overall research questions remain the same: I am curious how the habitat modifications that residents enrolled in the Bring Conservation Home program have made to their yards (removal of invasive plants, planting natives) influence larger scale patterns in avian functional and phylogenetic diversity. In addition, I am curious how these local features interact with larger scale patterns in urbanization to influence biodiversity. To help me answer these questions, I had selected 63 yards, located along a gradient from highly urbanized areas (e.g., in St. Louis City) to more suburban or rural areas (e.g., in St. Charles and Jefferson counties). A third of the yards have the highest Bring Conservation Home certifications possible (gold or platinum), another third are certified at a lower level (indicating less native cover, more invasive cover; silver), and the final third have not yet been certified (none)--serving as a more typical baseline yard with which to compare.

With the help of landowners, AudioMoth acoustic sampling devices programmed to sample bird and frogs will be deployed in each of these yards for the month of June. I'll collect the devices in July and begin the process of identifying all that we captured. And in doing so, I am diving head first into the world of bioacoustic sampling, and I am really excited about it! Follow me here for updates!

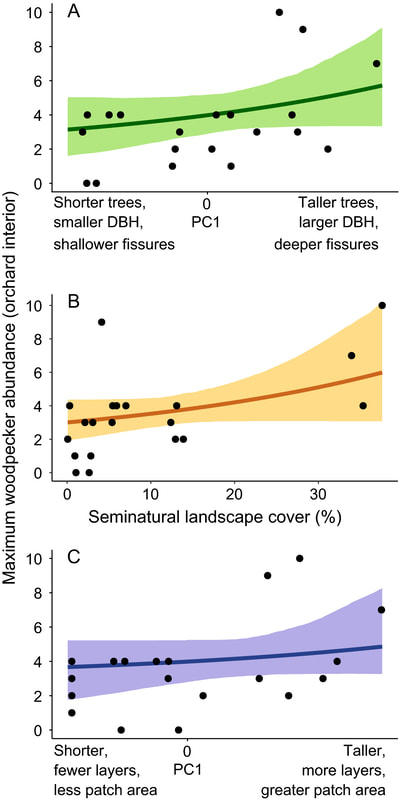

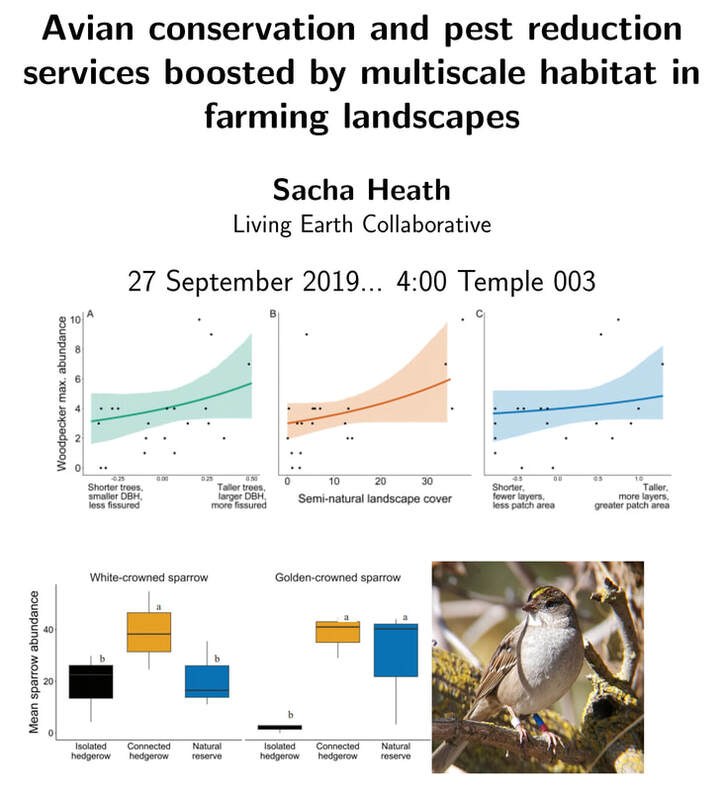

11% (caged) to 46% (no cage), and predation increased with increasing proportions of seminatural habitat within 500‐m of orchard transects. Predation also increased as the size and bark furrow depth of walnut trees increased, likely because these characteristics were associated with increasing abundance of avian predators with functional traits specific to consuming tree‐dwelling cocoons (e.g., woodpeckers). The presence and increasing complexity of local margin habitat increased the species richness and abundance of avian predators but was not predictive of cocoon predation. Consistent with intermediate landscape‐complexity hypothesis predictions, the effect size of woodpecker abundance on predation was large in simple landscapes (1–20% seminatural cover) and low in complex landscapes (>20% cover). Contrary to predictions, effect size was large in cleared landscapes (<1% cover), suggesting that orchards supported predators in cleared landscapes, with positive effects on pest reduction. We provide evidence that increasing the abundance of avian predators with traits specific for consuming target pests—by retaining old trees and seminatural cover—can increase orchard pest reduction services in an intensive agricultural region.

Gave a seminar about my dissertation research and a preview of the urban ecology research I have planned at the weekly seminar series of the Living Earth Collaborative and the Evolution, Ecology, and Population Biology program at Washington University, St. Louis. It was great fun and the audience asked many good questions. Also, the LEC has by far the best snacks of any academic seminar series I have taken part in.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed